Making Art – Episode 01

Lewis Miller

Episode Released 13th May 2018

I was standing in the lotto queue the other day waiting to make an investment in my long term happiness and watched as the woman in front of me spend $170 on her fortnightly flutter with her credit card. The guy behind the counter asked if she was going on holiday for a couple of weeks. No she replied, but as she left the shop she stopped, turned, waved her fistful of tickets in the air and with great optimism declared “I might be, and so might you.” Luck. It’s capricious, cantankerous and contrary. And despite it being a mysterious and totally abstract concept a great many of us are more than happy to engage in bizarre rituals dedicated to either acquiring good luck or avoiding the bad and some of us, it seems, are even prepared to borrow money and invest in a future based on getting it. Aside from being highly valued in the Lotto queue it’s worth having if you want survive a natural disaster or a wild animal attack and, judging by a lot of conversations I’ve had over the years, almost indispensable if you want a career in the creative arts.

Perhaps you too have been privy to one of those job counselling sessions, the ones that nearly always have a tone of grim reality about them and are peppered with an oversupply of foreboding and worn platitudes.

The career advisors I’ve met in bars and at backyard BBQ’s usually lead off with that old chestnut “Talent will out”. It’s a cliché largely reserved for the arts and is often employed as a knowing way of explaining someone’s success. When it’s offered as advice to the aspiring artist however it roughly translates as “if you’re lucky enough to have been blessed with some sort of genius you might just get somewhere”. In that context it’s nearly always qualified with “But you’ve got to be in the right place at the right time.” Which isn’t helpful because no-one seems to know exactly where that place is nor what time you need to be there.

And even if the conversationalist acknowledges your latent genius, admits that you’re roughly in the right place and commends you on your punctuality the exchange nearly always ends with a sort of extended voodoo blessing/warning. This takes the form of an ever so slightly pained stretching of the lips, a furrowing of the brow and a deep, painfully slow and uneasy intake of breathe. After what seems like an age, all that pantomime is followed by a heavy out breathe, a pause that’s slightly too long and then the weighted delivery of that granddaddy of all creative bon mots “But you’ve got to be lucky” which lands heaving at your feet as an implied fact.

What all this assumes of course is that hard work, the accumulation of knowledge and the acquisition of skills count for little in the arts and that artists, in any discipline, simply fumble about rubbing juju’s, looking at maps and keeping an eye on the time in the vain hope that one day their talent, if they have any, will lead them to create something startling that will somehow make the fairy tale come true. And while no-one would deny that sometimes chance is involved, that occasionally we do trip over twenty dollar notes lying on the footpath to think that most of our successful artists simply got wherever they are as a result of sustained good fortune is to do them and the arts more broadly a terrible disservice. Seriously, if I was a successful cosmetic dentist would you call me lucky?

So when I recently sat down with the Archibald Prize winning artist Lewis Miller and he told me that, at the time, he felt “lucky“ to have won what is arguably Australia’s most celebrated art prize I felt it was worth considering just how he got so lucky and precisely what luck means in this particular creative context.

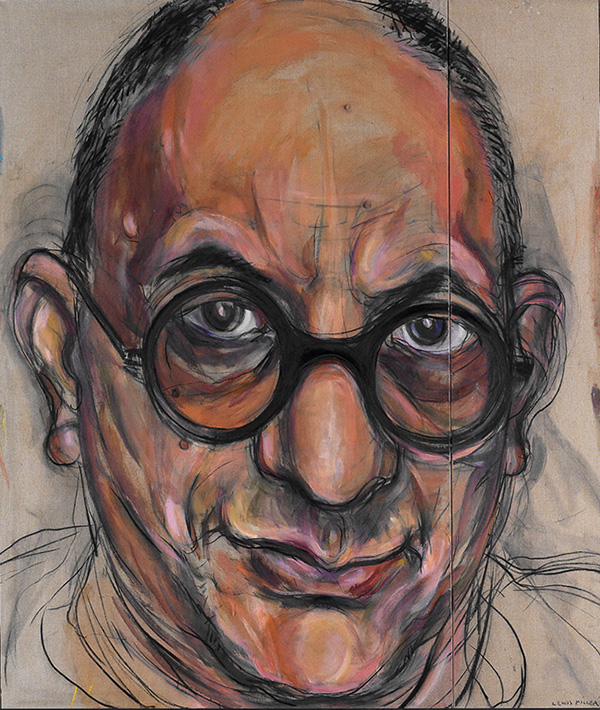

If you believe the hype, Miller burst onto the Australian art scene with his portrait of fellow artist Allan Mitleman in 1998. He had come from virtually nowhere and won the Archibald and in doing so he had become one of those people we love to hear about, he was an overnight sensation, a person that proves we can all be successful with a little luck. Like an actor who gets discovered standing on a street corner he’d chanced upon a paintbrush one day by divine intervention and in a blaze of dazzling, supernatural light stumbled upon the realisation that he had a talent for painting people. Unfortunately what’s missing from that particular narrative are a number of truths, the first being that Lewis had been drawing pictures of faces since he was a small boy.

Allan Mittleman No. 3

“I was always drawing as a kid. It was the class trick. It was a special thing I could do and of course then I would get the attention and be horribly embarrassed by it. Luckily in the 70’s I had long hair and could lean forward and my hair would cover my blushing.”

School for Lewis was a public one located in the south eastern suburbs of Melbourne. Home was a small, post war prefab concrete commission house on a large block in Chadstone. His father Peter was a painter in the social realist tradition who taught art at TAFE and his mother, Margaret, a housewife.

“Our house, I didn’t realise at the time, was extremely bohemian. We had draft resisters staying the night, friends with I guess drug problems staying over, people spying on my father because he’d been involved with the Communist Party. People playing guitars and singing folk songs. It was really amazing.”

It was at that house in the mid 60’s that Lewis first came into contact with The Archibald although at the time all it meant to Lewis was that he had to camp on the floor.

“Dad entered the Archibald and he hadn’t built his shed, his studio in the backyard at that stage so…all I knew really about it was that my brother and I had to move out our room so he had somewhere to paint this picture. I don’t know why he didn’t go again. It was a good picture.”

That picture was of Dr Max Upfal and was a finalist in 1967, the only picture Peter Miller entered in The Archibald. As luck would have it, 25 years later at a party in Dalgety Street St Kilda, Lewis was talking to a total stranger and telling him that he was a painter and that he’d just had his 4th picture accepted as a finalist in the famous portrait competition. He talked about his father having entered in the 60’s with this painting of a doctor Max Upfal and the fellow said “Oh. That’s really interesting.” When Lewis asked him why he thought it was so interesting he replied “Because Max Upfal was my father. I grew up with that painting.”

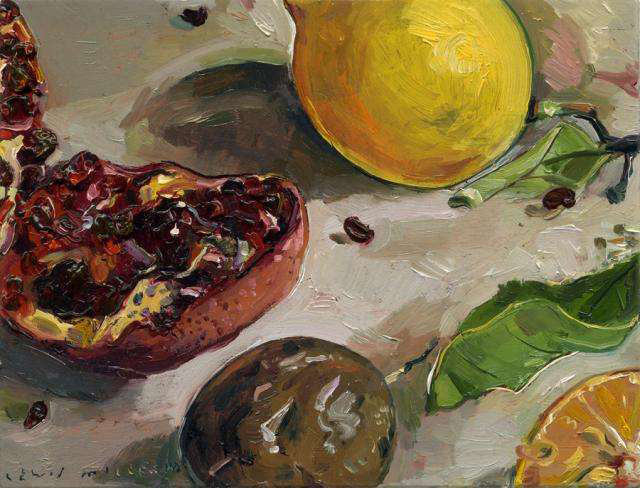

Fish Sea Snail

The relationship Miller shared with his father was incredibly strong. Peter would take the young Lewis with him on weekend jaunts into the country side to paint. “Dad would pull up on top of a hill in Donvale or somewhere and take out a piece of Masonite and start painting. I’d sit and watch. It was just what we did.” His father guided his son’s interest in the same gentle tradition that he himself had learnt at The Gallery School. “Master one thing and then move to the next.” So when Lewis had become proficient at drawing he was introduced to acrylic paints courtesy of sample pots arts suppliers had dropped off at the TAFE Peter was teaching at. At 14 Lewis attempted his first oil painting. “I was terrified. I knew I could draw but oil paint. It’s such a difficult thing to master.”

That first oil hangs on the wall in his studio. It’s a small picture, about 6 x 6 inches, painted from a sample cast of a section of Michelangelo’s David and Lewis is “… not sure how much of it I did and how much dad did. I suspect he did a bit.” By the age of 16 he knew he wanted to become a painter and so applied to go to art school. He admits to not “really being bothered” about the HSC because he’d already received his “Billy Elliot letter from the VCA” offering him a place at the then exclusive and prestigious art school. His parents where thankfully supportive.

“I was very lucky in that respect. I know a lot of people have to rebel against their parents. I remember dad saying “well you might make a lot of money, you might make none but it’s a good thing to do”.”

What followed was 3 intense years of deconstruction and reconstruction, 3 years about which Lewis has mixed emotions. “There was a lot of “Oh that’s so easy for you” and constant talk around the new. I remember in second year I think it was that Gary (lecturer Gareth Sansom) said that our year would produce only 1 and a half artists. I wasn’t one of the ones he named.” He tried rebelling against his father in terms of painting style and was even asked at one point to join The Roar Group, the small band of spirited young artists painting in a primitive, figurative style that emerged in Fitzroy in the early 1980’s intent on upsetting what they saw as the complacent Australian mainstream art scene.

“David (Larwill) asked me at a party in St Kilda. I didn’t know what I was doing. I was still living at home. But I think I knew I couldn’t paint like that…actually that I didn’t want to paint like that.”

Luckily another of his lecturers, Paul Partos, continued to encourage him but it was when a visiting lecturer, David Hurst, saw his still life and portraiture and simply said, “You’re good at that. Why don’t you just do that?” that the proverbial penny dropped. So when Lewis left art school he did so rather ironically as a rebel, one who eschewed the postmodern and conceptual art fashions of the time instead sticking to portraits and “plain things” as he refers to them. He then spent the next 10 years “just trying to paint.”

Fast forward to 1998 and Lewis has been graduated from art school for close to 20 years and steadily working on his craft. He has been fortunate to have received the support of the art dealer and gallery owner Ray Hughes who was impressed by Lewis’ point of difference as much as his skill. “I was lucky with Ray. A lot of gallery owner’s poo pood portraiture. Ray already had a couple of Archibald winners. He kind of understood it.” By 1998 he has already entered the Archibald 8 times, 7 times he’s been a finalist. “Up till then I’d been happy to be hung. It’s such a big event. Your picture’s on the wall at the Art Gallery of NSW. It’s very exciting. A hot ticket. But that year I remember lying in bed thinking, I should try and win it.”

Win it he did, but there was an element of good fortune attached to that win, good fortune that at the time seemed more like an impending disaster. He had initially approached Melbourne fashion icon Jenny Bannister to be his subject and she’d agreed. But then the work took an interesting turn. “I’d done an initial drawing of Jenny. But I couldn’t seem to get her over to the studio. We were getting closer to the deadline and I started to panic. What am I going to do? I though, my God, I’m going to have to sack her. So I did and rang up Allan.” Luckily Mitleman agreed. It was Lewis’ third portrait of Allan Mitleman for the Archibald, the previous 2 having been finalists. What was different? “The scale. It’s a pretty big picture. And Allan was great. He was very helpful…I’m not sure it’s my best picture. But you don’t often win things with what you think is your best picture.”

Winning meant that Lewis had the opportunity to travel overseas for the first time in 14 years. He intended to do a cooks tour of European art galleries and planned a visit to the Met in New York. Again chance stepped in. James Watson, the Nobel Prize winning biologist, co-discoverer of the famous double helix was in Sydney. Watson has a keen interest in art and was taken to Ray Hughes Gallery where he saw a drawing on Ray’s desk. It was a sketch Lewis had done of Ray on the back of Como Hotel letterhead “in biro I think.” Lewis’s well honed, classic style impressed Watson. “Who did this and can they come and do some drawings of me, my wife and 2 boys?” Lewis agreed and when the drawings were completed Watson told Lewis that since he was going to be in New York he should come to Cold Spring Harbor on Long Island and pop in to the laboratory.

Lewis did and while he was there he did some drawings of staff members and Watson asked him back. “He wanted someone to do these drawings and David Hockney was too expensive so he got me.” Over the past 20 years he’s been back several times to document the scientists that have been involved in the continuing research around the human genome. Over that time he has painted portraits of Watson and his fellow Nobel Laurites the late Francis Crick and Maurice Wilkins along with drawings of countless scientists, lab technicians and assistants. The culmination of that 20 years work came late last month with the launch in New York of the book Faces of the Human Genome.

So much has changed in that 20 years. Lewis now has an 11 year old son, William with his wife Marianna both of whom accompanied him to the launch. Those years have also seen him win the Art Gallery of NSW Sporting Portraiture prize the “Sportibald” with his portrait of AFL legend Ron Barassi, spend time in Iraq as an official War Artist, paint Sir Edmund Hilary, have a 60 second draw off with celebrated English artist Damien Hirst and complete a further 16 Archibald entries. In total Lewis has entered the famous prize 24 times and had his work hung as a finalist on 17 occasions.

Now that he’s a father he travels less and spends more time in the studio. “I’m lucky I can go every day. And I do. There’s always something to do. Stretching, varnishing. I never forget how fortunate I am. It’s a luxury I know. But painting is all about momentum, you’ve got to be doing it.”

Still Life

William likes to drop in and watch his father work. It reminds Lewis of sitting in the back shed watching his father who sadly died just 2 weeks after the Archibald win. “We shared the same concerns I think. We talked about Rembrandt and Picasso and Matisse and people like that. It’s easy to like those painters I guess but those things he showed me in those early lessons are still with me and are in some ways the ones I fall back on. How to mix colours and just a particular attitude to painting.” An attitude that came down in many ways to simply working hard at your craft.

On any given day you’ll find him in the studio doing just that, working on pictures, trying different things. Art, for Miller, is more a doing thing, a sensual experience rather than an intellectual one. “I just like to see how things work out. I’m a bit like Francis Bacon. He said, “I haven’t really got anything to say but I want to do pictures”. I’m not trying to say anything. I’m just trying to do something that might be good. If you can do something good, well, that’s very good. Very good.”

So would you say that Lewis Miller has been lucky? Perhaps. He certainly thinks so. He had a talent yes, but then he has spent his adult life dedicated to nurturing that talent. What might things have looked like had he painted Jenny Bannister for the 98 Archibald? Who knows? Was he in the right place at the right time? No. But his work was.

And that’s where the luck seems to come from because when you put down your juju and look at Lewis’s career you see that the good fortune has repeatedly come from the making, from a faithful dedication to the continuous refining of his craft and a quiet but sustained commitment to regular hours in the studio simply trying to be good. If it is luck it’s more in keeping with that described by the Roman philosopher Seneca who said “Luck happens when preparation meets opportunity.” Certainly Lewis has had opportunities but then he has also always been prepared.

Links

Below you can find links to further reading in reference to the interview.